Spontaneous and

Calculated

Story: Andy Julo

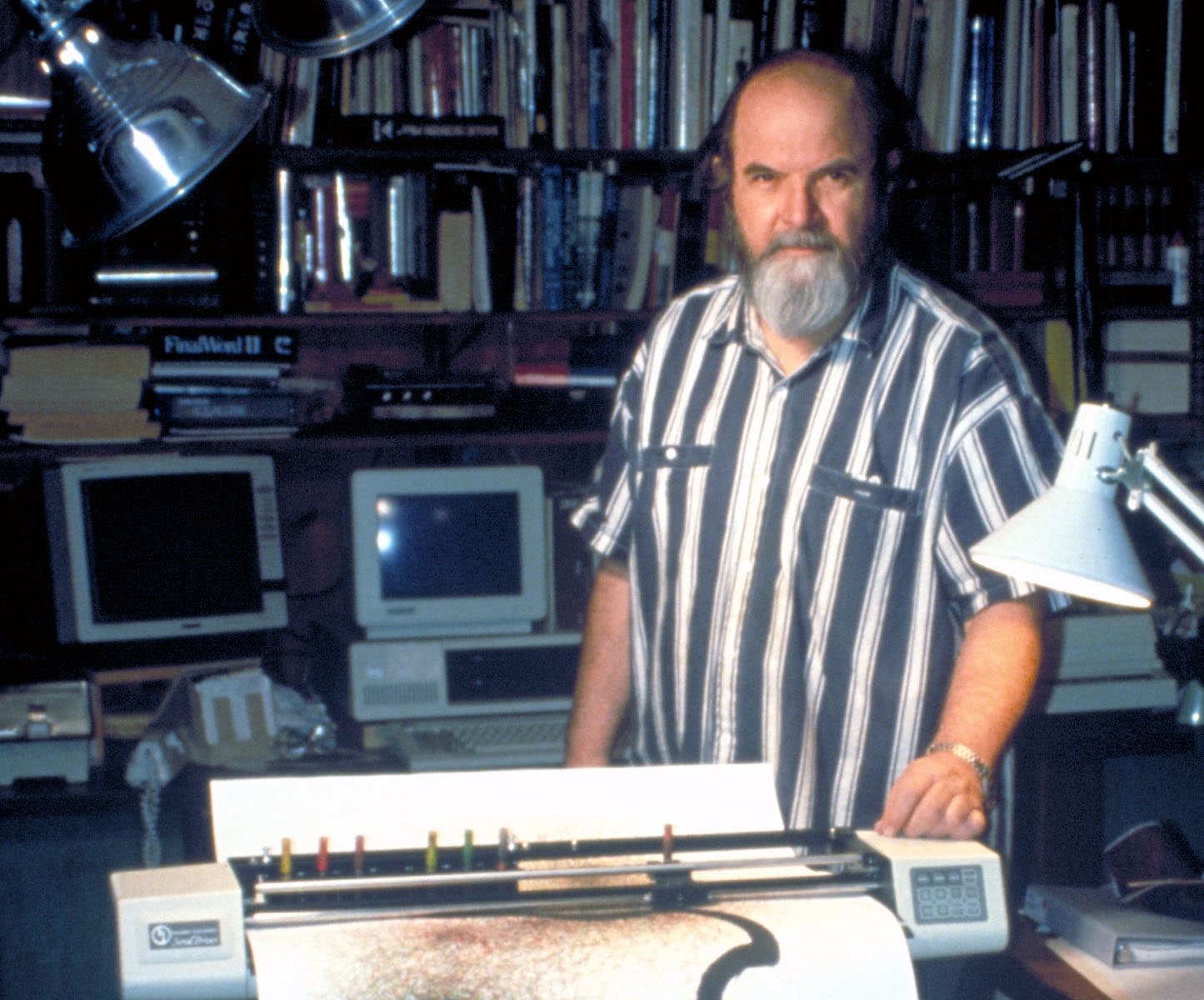

After working as an artist for over seventy-five years, digital art pioneer Roman Verostko passed away at his home in Minneapolis on June 1, leaving an indelible impact on the history of generative art and generations of digital creatives working around the world.

Before he began experimenting with electronic media, circuit logic, and computer languages in the early 1970s, Roman was a professed member of Saint Vincent Archabbey, a professionally trained painter, and a humanities scholar. Working at a time when art made in tandem with computers was viewed with deep suspicion, Roman anticipated the ways in which algorithmic procedure would revolutionize the world. Forming friendships with like-minded artists, Roman mounted exhibitions, organized symposia, and lectured widely on the ways in which code could be leveraged to create art reflective of the digital age. As an author and academician, Roman’s understanding of the historical and theoretical dimensions of art allowed him to articulate the efforts of generative artists to the public.

Weeks before the onset of the Great Depression, Joseph Victor Verostko was born on September 12, 1929, to second generation Slovak immigrants. One of eight children, he grew up in poverty within the coal mining community of Tarrs, Pennsylvania. Shortly after graduating from East Huntington Township High School, Roman enrolled at the Art Institute of Pittsburgh with the intention of pursuing a career in illustration. Here he learned the essentials of figure drawing, color theory, hand-lettering, and layout design.

While at the Art Institute, he visited his brother, Remigius, who had become a monk of Saint Vincent two years prior. Disillusioned with the highly competitive field of commercial illustration, he became increasingly interested in monastic life and ultimately presented himself as a candidate to the monastery on his twenty-first birthday, changing his name to Roman. As a young Benedictine, Roman was a voracious learner, earning a bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1955 before graduating from the Seminary in 1959. Encouraged to fuse his artistic training from the Art Institute with personal interests in philosophy, theology, and semiotics, Roman was commissioned by the monastery to create several projects on campus.

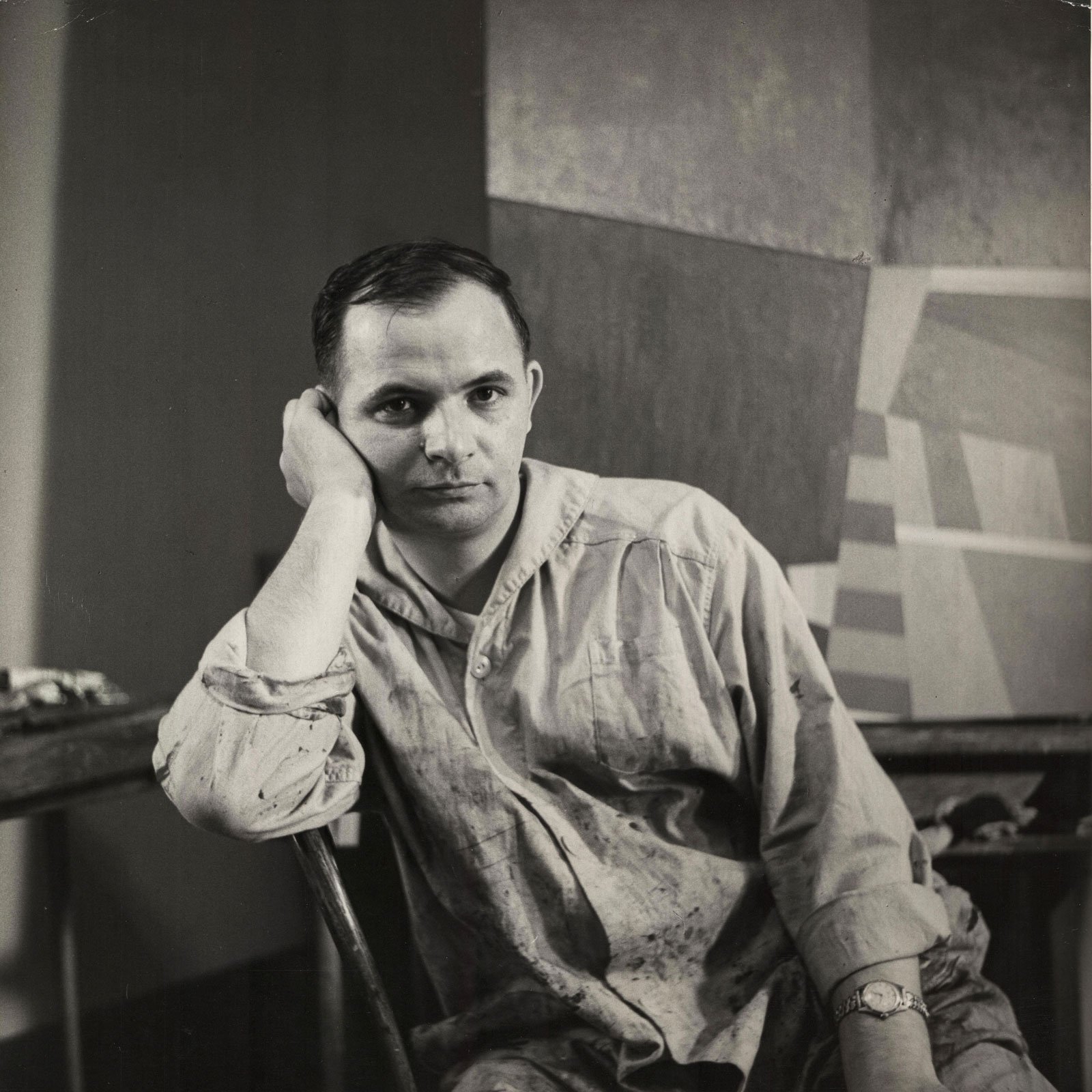

Shortly after he was ordained a priest, Roman was sent to New York to pursue advanced study in art history and studio practice. He took classes at New York University and Columbia before earning a Master of Fine Arts from Pratt Institute in 1961. Inspired by the work of twentieth century modernists like Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Kazimir Malevich who sought to integrate contrasting forces within their work, Roman developed an experimental practice of creating abstract paintings and drawings comprised of expressive, gestural forms. As part of that process, he experimented with automatism, an uncalculated technique of mark making that aimed to reveal subconscious thoughts and emotions. These works combine strategically-placed squares of saturated color with loose, gestural lines, emphasizing the need for balance between the rational and irrational, impulsivity and control. Rather than imaging a singular story or narrative, they are reflective of the process by which humans make decisions—each a meditation on the tensions between reason and feeling.

In May 1968, having confronted a crisis of faith, Roman left monastic life and married Dr. Alice Wagstaff, a child psychologist and university professor. The two relocated to Minneapolis, where he assumed a faculty position teaching liberal arts courses at what is now known as Minneapolis College of Art and Design. Over the next forty years, Roman and Alice would regularly collaborate on artistic projects in an endless pursuit of a shared creative life.

In 1970, Roman took a computer concepts course that included FORTRAN at Control Data Institute in Minneapolis. As an artist, learning to write computer code proved fascinating as the process permitted him to explore forms previously unseen. In 1982, Roman acquired an IBM PC. Shortly thereafter, he also obtained pen-plotters to execute abstract drawings guided by vast algorithmic procedures he had devised personally. Through countless hours of trial-and-error, Roman would revise his master drawing program, Hodos (the Greek word for path), to achieve increasingly sophisticated abstractions. After acquiring several pen-plotters and personal computers, Roman came to view his studio as an electronic scriptorium, with the plotters serving as electronic scribes, harkening back to the labor-intensive output of medieval monasteries who copied texts by hand before the introduction of printing technology in the mid-fifteenth century.

Roman’s work is typically characterized by layered, multi-colored self-simulated lines assembled into ethereal forms. While contemporary inkjet printing places dots of color next to one another, pen plotters draw lines over one another, resulting in a more luminous output. Roman was interested in creating curvilinear forms that were not visually beholden to the computer’s inherent grid system. Several bodies of work feature hand-applied gold leaf—a reference to the illuminated manuscript traditions of Europe and the Middle East. Singular among his contemporaries, Roman was intent to honor luminaries in mathematics and computing, including Norbert Weiner, Alan Turing, and George Boole, whose respective pioneering scholarship was pivotal in the development of future computational technology.

Together with Jean-Pierre Hebert, Roman co-founded the Algorists in 1995. As with any twentieth century art movement, the Algorists had a manifesto, written by Jean-Pierre fittingly as an algorithm. This was a significant gesture as it helped to codify those working with studio practices grounded in rules-based logic. Despite staunch resistance from art curators and critics who maintained computer-assisted drawing would never be considered art, the Algorists remained resolute. It is at conferences like SIGGRAPH, ISEA, and Ars Electronica that these artists found a home, a place to share their ideas, forge connections with like-minded others, and exhibit their work.

At the end of his life, Roman’s work had appeared in over 100 exhibitions on five continents. His work is represented in institutions globally, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Digital Art Museum in Berlin, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Tokyo’s Tama Art University Museum, and the Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany.

In November 2021, Saint Vincent College dedicated the Verostko Center for the Arts in honor of Roman. Located inside the campus library, the 9,000 square foot state-of-the-art facility features four distinct exhibition areas, a video-presentation space, administrative offices, and climate-controlled storage for Saint Vincent’s collection of art and rare books, as well as the College’s archive. Dedicated to featuring artwork that investigates intersecting academic disciplines, the Verostko Center stands as an enduring testament to Roman’s lifelong work of revealing the existent power when fields of inquiry converge. Saint Vincent proudly holds the largest collection of Roman’s work, spanning the entirety of his career, ranging from commissioned murals and interactive sculpture to pen-plotted drawings and time-based media projects. The Verostko Center is also home to Roman’s personal archive—an extensive repository of materials for scholarship and curatorial projects, made available simply by contacting the Center.

Roman believed that the best work out there involved risks, that art was an indispensable tool in navigating life’s most enduring questions. As someone who was raised in the shadow of industry, Roman went out to become one of the prophetic witnesses to the Algorithmic Revolution. He was a tireless advocate for artists whose methods, deemed too strange or experimental, would ultimately bring us to the place where we find ourselves today. Perhaps the best way to honor the creative legacy of this seminal artist and son of Saint Vincent is to pay close attention to the world we inhabit and the one that lives inside us. Cultivating our curiosity and sense of wonder that asks, What else is possible?

“Every human person bears within herself a jewel-like capacity—

an imagination, a living spirit

—which often lies dormant, unable to break through the busyness of everyday life.”

- Roman Verostko, 1972